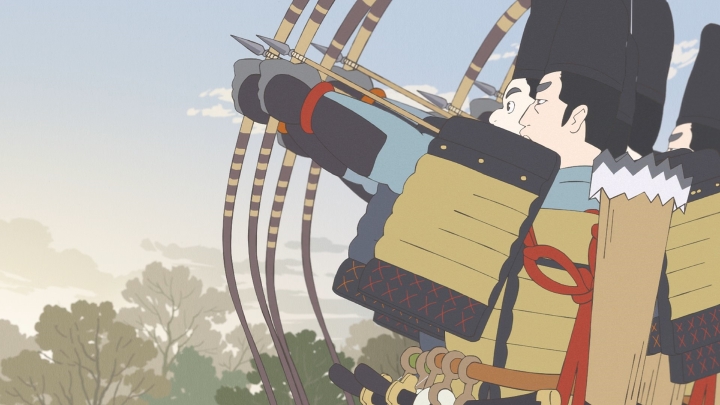

The year is 1181. Not long after achieving political dominance in western Japan, the Taira clan’s power has already begun to fade. Their move to Fukuhara is short-lived, and the capital returns to Kyoto a mere six months after its relocation. Interpreting this return as a sign of aggression, the warrior monks of Nara engage the Heike in combat, but suffer a great loss when their temples (as well as a massive Buddha statue) are burned in the course of the Heike’s retaliation. Kiyomori, who gleefully welcomes news of the burning, is struck with karmic payback in the form of an unquenchable fever, which ultimately leads to his death (and condemnation to the lowest level of hell). His son Munemori, by the anime’s account a rat-faced sycophant, intends to succeed his father and honor his dying wish: to have the head of enemy commander Yoritomo hung before his grave. But provinces to the north, east and west are all allying themselves with Genji forces, painting a bleak picture of the Heike’s military prospects, and indeed, their continued survival.

All this, and yet the series returned in this episode to its consideration of women’s place in Heian society, with Tokuko as its star player. It reminded me quite a bit of the show’s second outing, where two shirabyoshi who served Kiyomori became nuns to escape his employ. Tokuko threatened to do the same thing this week, producing a knife (which she’d been hiding in the folds of her clothing) and holding it to her hair as leverage in a dialogue with her father. This drastic display was prompted by Kiyomori’s ugly request: that in light of her husband’s illness, she allow herself to be wed to her own father-in-law (Go-Shirakawa) to increase the Heike’s political security. I’m sure this read like an audacious request to most modern-day watchers, especially since Tokuko’s father forced her into her original marriage, as well. But as this series has repeatedly made clear, even women of high station had little control over the broad strokes of their lives during the Heian period (and, if I may speculate, for many centuries afterward). The fact that Tokuko was carrying a knife at all speaks to her awareness of a need for protection, be it from Genji warriors, courtiers who might put a hand on her, or the demands of her own father. I wonder if that knife might reoccur in the future, given that it’s not only Tokuko, but the Taira at large who must defend themselves at this point.

It wasn’t only Tokuko’s threat to renounce the world that put me in mind of the series’ second outing. Given her refusal to marry Go-Shirakawa, a new bride was found for the former Emperor: Miko no Hime-gimi, another of Kiyomori’s daughters. As in the tale of the two shirabyoshi, where Gio was forced to act as a companion for her replacement Hotoke-Gozen, Tokuko was asked to be a conversation partner for her half-sister. The emotional dynamics are not the same – Gio was heartbroken at losing her position, while Tokuko purposely secured her freedom – but the pattern of men requiring the service of other women to entertain their own partners is consistent. The show even invoked the lotus flower, a symbol of enlightenment, in both episodes. Both Gio and Hotoke-Gozen sought this enlightenment in Buddhism, and Tokuko appears to do the same; the song she sings at the episode’s end references multiple concepts from Pure Land Buddhism, including the five obstructions to women’s attainment and the story of Longnü, a dragon girl who achieved enlightenment in spite of those obstacles. Tokuko’s determination to become “the flower that blooms in the mud,” finding fulfillment despite the challenges resulting from her gender, strikes me as similar to Longnü’s attainment of the Buddhahood despite the belief that it was impossible for women.

I’m sure there were many Buddhist concepts scattered throughout this episode, but as I’m far from a scholar, the only one that I caught outside of Tokuko’s story was that of Avici, the lowest level of Nakara (a rough equivalent of the Christian hell). Kiyomori’s wife was visited in a dream by Ox-Head and Horse-Face (yes, those are their real names), who declared their intent to send him to Avici for his burning of the Nara temples. It was actually his son Shigehira whose misfortune resulted in a fire spreading to the temples, at least in this version of the tale, muddying the appropriateness of Kiyomori’s punishment. His character was generally muddy, I found, until the moment of his death – after demanding that Yoritomo’s head be hung at his grave, his last words were, “I wonder if Tokuko is still upset with me.” There’s certainly room in fiction for a warlord to express regret at the end of his life, but looking back, there was more whimsy than nuance in the occasional diversions from his warmongering persona. Moments like his rationale for consolidating power in episode 6 hinted at a much more thoughtful man than the one we ultimately got from this adaptation, which will certainly be one of my main criticisms when the show wraps up next month.

But before the show wraps up, it must conclude the Genpei War, which history tells us is still four years from ending. Notably, Biwa has been banished from the Shigemori family estate, with Sukemori playing the villain and sending her away for her own safety (no doubt he sees the writing on the wall for the Taira clan). She leaves in the winter, carrying only her lute and the white-haired cat she met at the tail end of the previous episode – as a final Buddhist note, I wonder if the cat is supposed to be a reincarnation of Shigemori. Last week it led her to Koremori in the midst of his anguished training (perhaps encouraging her to relieve his son’s suffering), and here it made the journey with her from Fukuhara to Kyoto as the capital returned to its original spot (perhaps to stay close to its family). It’s just as likely that the cat’s white fur is meant to match the hair of the lute priest that Biwa will eventually become, but as Shigemori’s virtuous character would likely have kept him out of Nakara, it’s possible that he returned to life as an animal in order to accompany his adopted daughter on her own journey of enlightenment. With no place to call home, where will Biwa go? That uncertainly has rekindled my interest in her story for the first time in a long time, so I hope she lands in a place that will serve her character well.