The year is 1184. Having fled Fukuhara to escape Genji troops, the Heike are forced to undergo several further relocations in order to avoid their pursuers. In the meantime, Go-Shirakawa returns to the capital and crowns a new Emperor in Antoku’s absence, thus undermining the Heike’s plan to return to their former influence. Go-Shirakawa is not without opposition in Kyoto, however; the Genji general Yoshinaka captures him in a bid to strengthen his control of the capital. Yoshinaka plans to launch an attack on his cousin Yoritomo and make himself head of the Genji, but Go-Shirakawa sends a messenger to alert his would-be victim of the plot. With this warning in mind, Yoritomo assigns his calculating half-brother Yoshitsune to attack the capital, resulting in Yoshinaka’s death. As this Genji infighting plays out, the Heike return to Fukuhara and make a stand at the Battle of Ichi-no-tani, but are outmaneuvered and forced to flee once more, their troops having been reduced to a mere 3000.

That’s not the longest stretch of time that Heike Monogatari has covered in a single episode, but it’s certainly the most densely plotted – much of the conflict within the Genji family had to be abbreviated to make everything else come together. Yoshinaka’s untamed charisma and military brilliance practically made him the hero of the previous episode, but here his ambition to unseat his cousin was reduced to a comical footnote, with loopy electric guitars accompanying his request to be named Shogun (along with questions regarding his sanity). His death was perhaps the series’ biggest anticlimax thus far, owing to the lack of detail surrounding the familial power struggle that preceded it. Yoshitsune wasn’t shortchanged quite as severely, since the anime communicated his ruthlessness with cool color choices and a brief but icy vocal performance. His prominence came on too quickly for my liking, though, since he was introduced only minutes before his victories over both Yoshinaka and the Heike.

This series has made similar compromises before, and given the mismatch of its massive story and miniscule episode count, they’re easy to understand. But Heike Monogatari’s biggest fumble yet has nothing to do with adapting an epic for the small screen; rather, it’s about Biwa’s reunion with her mother Asagi, a plotline invented specifically for this adaptation. After the premiere opened with her father’s murder, you’d figure that her quest to meet her only living parent would be of paramount importance, if not narratively then at least emotionally. But their meeting came and went in the most ordinary fashion, with no context given to her mother’s decision to abandon her child beyond ‘going to live with another man.’ Asagi’s wish for Biwa’s father to “rest in peace” tells us that she shares her daughter’s clairvoyant eyesight – how else would she have learned of his death? – but the staggering implications of this fact weren’t explored in the least. We were locked into Biwa’s point of view the whole time, with her acceptance of her mother’s failings as the scene’s unwavering destination. Their supernatural connection, Asagi’s blindness, the likelihood that she foresaw her lover’s death and left to spare herself that pain – the series kept too tight a lid on all of these ideas, and the result thoroughly disappointed me.

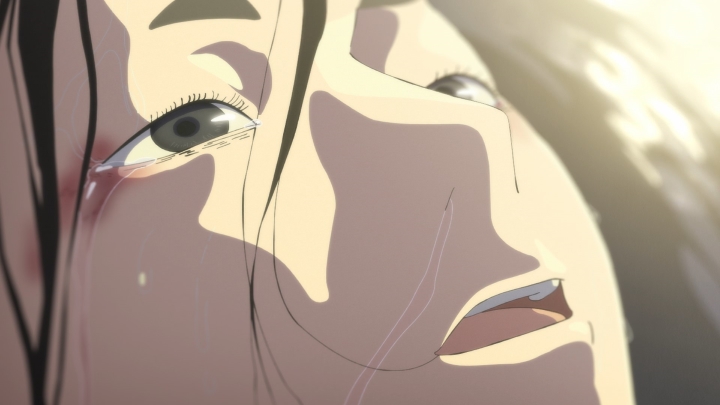

Salvation for this episode arrived at its conclusion, though, in Atsumori’s duel with Kumagai Naozane. Heike Monogatari’s obligation to its primary characters has left little time for Atsumori to develop beyond the impressionability of his youth, but this turned out to be for the better, as it meant he could cling to concepts like nobility and honor even as Kumagai held his life in his hands. Atsumori’s resolve to die a virtuous death echoed his promise to Kiyotsune, whose earlier suicide was motivated by a loss of faith in the Heike’s cause. In essence, Atsumori wanted to prove to his fallen friend that honor was of paramount importance, even in the face of defeat. And yet, he ended up joining him in this metaphorical representation of their two souls (contrast that shot with this one of just Kiyotsune shortly before Atsumori’s death). He may have maintained his philosophy to the bitter end, but Atsumori received no greater reward for his virtuous death than Kiyotsune did for his shameful one. These weighty concepts are one of the things I most enjoy about this show; the cinematography is another, and boy was it fantastic here. The frenzied expressions on the combatants’ faces as they fought, the way the light played across the water as Atsumori rode along the shore, the shallow focus effect on his face as he made peace with his death – beautiful stuff. This is one of the scenes for which I’ll remember Heike Monogatari years down the line.